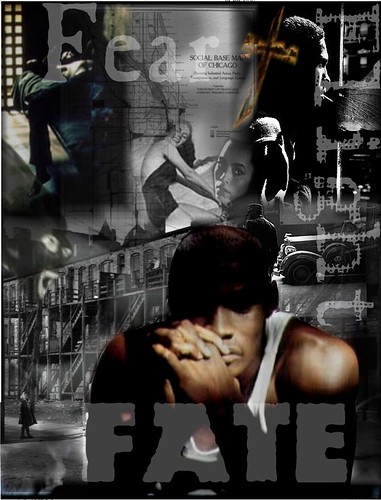

"Native Son Montage" digital montage 11"x14" 1997

I remember seeing the movie version of Richard Wright's Native Son when I was about 12 years old. I found it incredibly depressing. A few years later, when I was 16, I had to read the book for English class. And then I had to read it again in college for a freshman year humanities class. For those of you who read last week's From The Archives, it was the same class that I did the Venus Hottentot Montage for. I once again had a chance to showcase my digital collage skills. Of course, I couldn't get away without writing about what I created. Here is what I had to say about this piece:

My Native Son montage depicts Bigger’s final contemplation of himself and his life. Up until the very end of the book, Bigger has no inner life. Like Fanon’s native, because he lacks an inner life, Bigger “does not commit suicide. He kills.” But there are a few fleeting introspective moments when, twenty years old and about to die, he begins piecing together elements of his life. This state of mind is portrayed in the montage by the shadowed face of the man in the foreground.

Etiological elements of Bigger’s development are pictured in the background, including a photograph of run-down depression-era Chicago tenement houses. At the top center of the picture is a Great Migration era “Social Base Map of Chicago,” which shows the racial makeup of neighborhoods around Chicago. This represents the extreme segregation of the so-called “City of Neighborhoods,” which resulted in the “locked-in life of the Black belt areas” that Wright describes in “How ‘Bigger’ Was Born.”

The images I selected of Mary and Bessie portray them both as living. At first I considered using pictures of them as corpses, primarily because of Bigger’s responsibility for their deaths. Yet I realized that Bigger spends little time at the end of the novel contemplating their murders. He is no longer haunted by the image of the severed head or the bludgeoned body. This was why I chose pictures representative of the two young women’s personalitiesMary carefree and smiling in a scene reminiscent of her newsreel portrayal, and Bessie looking downtrodden and miserable. To the left of Bessie and Mary is an image representative of Bigger’s job as a chauffeur. Above it, Bigger looks out of a broken window in an abandoned building as he hides from the law. The personage in blackface sweeping down upon him like the wailing ghosts of Picasso’s “Guernica” symbolizes the pervasive racism of the time. The burning cross at the top embodies Bigger’s struggle with racial hatred and his own hatred of Christianity and its cross. Lastly, the words “Fear,” “Flight,” and “Fate” are strategically placed in the montage. With his fear and flight behind him, the only thing that Bigger has ahead of him is his fate.

My Native Son montage depicts Bigger’s final contemplation of himself and his life. Up until the very end of the book, Bigger has no inner life. Like Fanon’s native, because he lacks an inner life, Bigger “does not commit suicide. He kills.” But there are a few fleeting introspective moments when, twenty years old and about to die, he begins piecing together elements of his life. This state of mind is portrayed in the montage by the shadowed face of the man in the foreground.

Etiological elements of Bigger’s development are pictured in the background, including a photograph of run-down depression-era Chicago tenement houses. At the top center of the picture is a Great Migration era “Social Base Map of Chicago,” which shows the racial makeup of neighborhoods around Chicago. This represents the extreme segregation of the so-called “City of Neighborhoods,” which resulted in the “locked-in life of the Black belt areas” that Wright describes in “How ‘Bigger’ Was Born.”

The images I selected of Mary and Bessie portray them both as living. At first I considered using pictures of them as corpses, primarily because of Bigger’s responsibility for their deaths. Yet I realized that Bigger spends little time at the end of the novel contemplating their murders. He is no longer haunted by the image of the severed head or the bludgeoned body. This was why I chose pictures representative of the two young women’s personalitiesMary carefree and smiling in a scene reminiscent of her newsreel portrayal, and Bessie looking downtrodden and miserable. To the left of Bessie and Mary is an image representative of Bigger’s job as a chauffeur. Above it, Bigger looks out of a broken window in an abandoned building as he hides from the law. The personage in blackface sweeping down upon him like the wailing ghosts of Picasso’s “Guernica” symbolizes the pervasive racism of the time. The burning cross at the top embodies Bigger’s struggle with racial hatred and his own hatred of Christianity and its cross. Lastly, the words “Fear,” “Flight,” and “Fate” are strategically placed in the montage. With his fear and flight behind him, the only thing that Bigger has ahead of him is his fate.

No comments:

Post a Comment