Though you can see the pictures in my book very clearly in the online preview, it isn't easy to read the text. So with that in mind, I'd like to share an excerpt with you.

Trial and Error

My course of study at Governors State began rather inauspiciously. In a frenzy to make up for lost time, I tried to do too many things at once. I took on a new full-time job that was far from home; I was taking two graduate courses at a university that was also far from home; and I was trying to find a way to buy my first home. All my time was consumed with studying, learning the new product lines I was selling at my new job, learning African art history, and learning about all the things that were wrong with the foreclosed fixer-uppers I was considering. Too little of my time was devoted to what I needed to figure out as soon as possible—my preferred painting style.

I needed to develop a body of work, and it needed to be cohesive enough to come together as a graduate show. I needed to choose a unifying theme. The theme of displacement was the one that appealed the most to my sensibilities as a frustrated yet hopeful first-time home buyer. Chicago was nearing the end of an era in which it seemed like every possible vacant structure—be it a factory, hospital, school, or warehouse—was being converted into condominiums that I could not afford. I found the prospect of it quite distressing.

Perhaps I have always had a keen sensitivity to exclusion. I grew up academically cloistered, spending my school days with other gifted students from kindergarten through high school, and I never felt like I belonged anywhere once school was out. Sometimes, even amongst my peers I felt out of place because I was more interested in art and creative writing than math, science, and computers—the three subjects that seemed, to some of my teachers and the world at large, to be the most important interests that a gifted student should have. I attended a church whose strict teachings warned parishioners to shun “worldly” things. We were admonished to be “in the world but not of it.” My experiences often made me wonder whether I was meant to fit in anywhere.

I felt as though I also was being locked out of my chosen profession of interior design, that my very career was being displaced. In the year that had passed since graduation, I had not acquired a year of work experience with a licensed interior designer, and as a result, I was not on track to being able to call myself an interior designer. Instead, I was working parallel to my chosen field, admiring it from a wistful and seemingly ever-growing distance. I knew I could be a great designer, but nobody would give me a chance. My quest to become an interior designer had started to seem like yet another reason for me to feel like an outsider looking in.

I felt alienated from the job market in general. Even with two college degrees, I felt like no human resources person outside of a department store would let me get my foot in the door because I lacked experience. So many entry-level jobs were being outsourced overseas or eliminated completely, and it seemed my options for employment were dwindling every day. And so, I felt an empathy and a kinship for those with no place to go, because that was how I felt as well.

Yet, I had a hard time translating this sense of displacement into a visual language. I ambitiously had begun a 30” x 40” oil painting of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, but the temptation to go back to painting in the abstract style which I developed in my undergraduate painting class was always there. Often, I succumbed to that temptation and put the Hurricane Katrina painting aside to work on pieces that picked up where Katrina left off. An abstract, monochromatic canvas seemed a welcome respite from the chaos unfolding amongst my Turpenoid-spattered evacuees. Working in an abstract style felt right to me, yet I lacked confidence in my artistic instincts.

|

| Heckuva Job | 30"x40" | oil on canvas | 2007 |

|

|

| Untitled (Green) | 30"x40" | oil on canvas | 2007 |

Pulled in different directions, torn between keeping the commitment to work in the style I had proposed to work in and following my inclination to work with corrugated cardboard and other found objects, I created an assortment of paintings that seemed at odds with each other. Each had the kernel of an idea, but none of them explored the idea in depth. My energy was too scattered between work and school, and my lack of focus was reflected in my art.

During the final week of the summer term, after a harrowing final exam in my art history class and an anguishing final critique in my painting class, I was dealt a final

coup de grace when my new job fired me after less than two months for “not making connections with the customers.” When I got home and checked my voicemail I discovered that I was getting an incomplete in my painting class. I may not have had a second chance to be a design consultant, but at least I would have a second chance to prove myself as an artist. I went back to selling carpet, which is the job I had held before the one that fired me. After having a taste of working as a designer, having to go back to selling carpet felt like a demotion. I had fallen back into the rut I so desperately had tried to escape. What had been the point of design school? Had it all been a waste of time?

The one good thing about my carpet sales job was that it was much less demanding of my time and energy. Sales were slow and downtime was plentiful, so when I had finished my reading for school, I used the extra time to read books on subjects that interested me, and to write about my frustration with working in retail.

8-28-07

It is a totalitarian regime, complete with uniforms: all black. Far from chic or modern or cutting edge, it just looks drab, makes the men look like androids, the women appear matronly. It is not a seductive black, or a mysterious black—not even a powerful black. It is an unimaginative, uninspiring, dehumanizing black. There is no music. There is no natural light. The bulbs in the track lights are dim. There are clocks, but they all display the wrong times. Nobody wants to be here.

For six years, my resentment towards working in retail had been building, but my most recent experiences had deepened my awareness of my displeasure with the work I was doing. My job was my largest time commitment, and I felt as though I could not be myself when I was there. My interactions were scripted. I constantly was being compared to other salespeople. I felt as though we were all being judged on our ability to sell people things that they did not need. Being surrounded by beautiful things I could not afford was utterly tormenting.

I felt powerless in my dealings with abusive customers. They were always right, so how could I ever stand up for myself? Anyone, it seemed, could just come in from off the street or call my department on the phone and start giving me orders, and I would have to take them; if they did not like what I had done, they even could report me to the management and try to get me fired.

In this retail environment, I was disposable and replaceable, not unlike the cardboard boxes that the merchandise was shipped in, or the plastic bags that the customers carried out of the store. It was a brutal existence, yet all these things were made necessary by consumerism.

Ironically, it seemed as though my own desire to create was sublimated into a desire to consume. I still was obsessed with buying a home, and still working full time so that I could do it. Though I then had plenty of time to read, I still had not set aside time to work in the studio so that I could finish my incomplete paintings.

I found a new source of inspiration when the fall trimester began—a creativity class that used The Artist’s Way as one of its texts. I became more aware of the negative thinking that was holding me back, and also became more open to new ideas as I took time to seek them out. The art and design magazines and books I read, art shows and film festivals I attended, and other artists I interacted with awakened my creative yearnings. More attuned to my true desires, I began to realize what kind of art I wanted to create. At the same time, I also began to see that my overloaded schedule—working full time at a job I despised, taking an interior design course in addition to my graduate work—was preventing me from working in the studio frequently enough to make any progress. It was my job that had made me become, in the words of Mihalyi Czikszentmihalyi in

Finding Flow (a book I was reading for my creativity class), “materially comfortable but emotionally miserable.” I came across a thought-provoking question that Daniel Pink had posed in another book I was reading,

A Whole New Mind:

“If you knew you had at most ten years to live, would you stick with your current job?”

My answer was, “Absolutely not!”

I began to suspect that I had been working too much in order to avoid making art. My longing for time to make art became greater than my desire to become a homeowner. For the first time, I allowed my art to become a priority in my life. So, when I found an opportunity to work part time at a nonprofit, I quit my job selling carpet.

I still had a few more weeks left before the trimester was over, and I used my newly-earned free time to work on my art. I finally was able to immerse myself in my art because I had been freed from my fear of being an artist. It was then that the real work on the Post-Consumerism series began with the creation of

Smother.

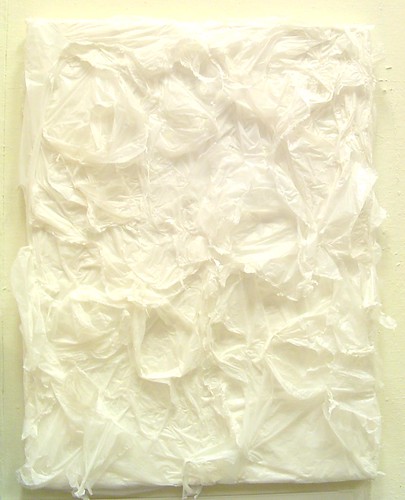

It is unusual for me to think of both a title and a concept simultaneously. So often, one precedes the other, but in the case of Smother, the title came to me because I was feeling emotionally smothered. Giving the piece that title was a way for me to push back against the negative influences that threatened to overpower me in my personal life and in my job. I saw it as a form of resistance.

The concept, a field of white plastic shopping bags splayed open and arrayed on a canvas and wood support, was inspired by both the dire warnings of accidental suffocation printed on the sides of the bags and the disastrous impact of plastic bag waste on the environment. The irregular shapes of the bags and their translucency give them a cloud-like quality. The piece is imbued with a sense of the ethereal.

The use of a common disposable object in a work of art, to me, is a symbol of transcendence. It was indicative of the transformations taking place in my own life as I became more aware of my negative thoughts and emotions, and found new ways to grow beyond the pain they had caused me for so long.

Once

Smother was complete, I finally realized the direction in which I wanted my art to go. Better yet, I no longer had an incomplete in my first studio class of grad school.

|

| Smother | 40" x 30" | plastic bags on canvas | 2007 |

Want to find out what happened next?

Buy my book! It's available in softcover, hardcover, and as an e-book for the iPad. Save 25% when you enter the coupon code JUMP at checkout.